Paths

Also Known as/Related

- file paths

- pathing

- resource location

Many times when you are writing a program you will need to find something. For example you will need to open a file to read it’s contents, or send users a page based on their URL. All of these situations are a problem called resource location, and paths are the way that people encode solutions to resource location issues. For example a file path will tell you where you can find a file on a system. There are tons of different types of paths, but we will look at 2 common examples and cover some gotcha’s with them.

File paths

File paths use a delimiter encoding (\ on windows and / on macOS/linux), what this means is that you have containers (folders/drives) and items (files). Items are stored inside containers, along with other containers (we have drives with files/folders, and folders with files/folders). When we are telling someone how to access a file we write it in the form of container<delimiter>container<delimiter>item, so if we had a file called readme.md inside the C:// drive, inside a folder called projects, we would write C://projects/readme.md.

💽 C://

└── 📁/projects

└── 📃readme.md

In python you will primarily use the os.path module, shutils and/or pathlib to work with files and paths.

Extensions

There are many different files, and because of this we need a way to differentiate between them so we know which program to open. Extensions are a little indicator that comes after a file name to indicate what type of file it is. For example readme.md indicates the file is a markdown file because it ends with .md. Please keep in mind extensions guarentee nothing. They are just text, and anyone can change them. This means if you have a .txt file, all you have to do is change the filename to .md for it to be considered a markdown file. They just exist to let people know what they probably should treat the file as, and allow you to register default applications to handle certain extensions to make opening files easier.

Common notation

When looking at file paths there are some common formats people will follow:

- Folders will usually contain a delimiter to differentiate them from files. For example

/projects or projects/. Some people don’t do this, and if there is no file extension it’s usually safe to assume people are talking about a folder - People will use

/ and \ interchangeably, but \ will only work on windows, and / will often work on windows, but not always. It depends on the language. For python you can always import the os package, and use os.path.join() or os.sep - Windows and macOS/Linux have special characters and ways of defining variables. Since absolute paths are so long, there are some shortcuts people use to get to common folders. For example on macOS/linux, you can get to the user folder with

~. So if you want an absolute path to the desktop, you can use ~/Desktop, if your user is kieran this would expand to <drive>/users/kieran/Desktop. The same is possible on windows using %USERPROFILE% (expands to <drive>/users/<username>), so %USERPROFILE%\Desktop would always get you to the desktop. - There are tons of reserved characters for paths that can’t be used. For example you can’t have

/ in a folder name, since there would be no way to tell if it’s a delimiter or part of the name. The simplest thing to do is to only allow letters, digits and parenthesis () and square brackets [], everything else should be removed from paths. In python you can do this by importing the string module and using something like this:

import string

path = "" # Some path here

legal_path_characters = string.ascii_letters + string.digits + "()[]." # Allowed characters in file path

path = ''.join(current_character for current_character in path if current_character in legal_path_characters)

Relative vs Absolute paths

Up until this point we have been using absolute paths when talking about files. Absolute paths give you exactly where things are. It tells you which drive to look in, and exactly which folders. The advantage with this is that you can find what you’re looking for from anywhere on the computer. But they can also be long and unruly to deal with. For example here is the link to this page on my computer C:\Users\Kieran\Desktop\development\ignite\website\content\dictionary\paths.md.

But what if I currently have the /website folder open? Why do I have to go back all the way and parse all of C:\Users\Kieran\Desktop\development? I could just skip that whole part. Relative paths do exactly that. When you run a script, or a file from a terminal your terminal already has a location open in order to read the file. Relative paths use your current working directory (cwd, or the folder you’re in currenly) to make paths easier to work with. This is handy because it’s shorter, and also it helps avoid problems with if you rename a directory. If I were to rename the project from /website to ignite-site the entire absolute path would break, but if I assume I’m already in that folder when I’m running the command, it doesn’t matter!

Relative paths have a couple of special characters they use:

. This is your current folder you are in (cwd).. This means “go up a directory”. So if you have an absolute path C://folder-1/folder-2/python.exe, and you are inside /folder-2, you can use .. as a relative path to /folder-1

File handling

When using files in a language it’s important to keep in mind that you have to follow a few steps:

- Find the file (get the path)

- Open the file

- Close the file

If you forget to do the last step then you will often find yourself unable to open the file with other programs. To do this in python you would do:

f = open("filename.txt", "r") # Open the file in read-only mode

print(f.read()) # read the file contents and print them

f.close() # Close the file

This seems fine, unless you have an error in the middle:

f = open("filename.txt", "r") # Open the file in read-only mode

1/0 # Causes a ZeroDivisionException

f.close() # Close the file

Then f.close() is never called! Python will sometimes fix this by closing all of the open files for you when a program crashes, but this is not guarenteed, especially if you do something like this:

f = open("filename.txt", "r") # Open the file in read-only mode

try:

1/0 # Causes a ZeroDivisionException

f.close() # Close the file

except:

... # Do stuff

Now the file won’t close until the program fully terminates since the error was ignored. Instead we can do something a bit safer:

with open("filename.txt", "r") as f:

print(f.read())

The with statement (called a context manager) means that once the code exits the indented block it will close the file, and also will ensure it’s closed if an error happens!

URL’s

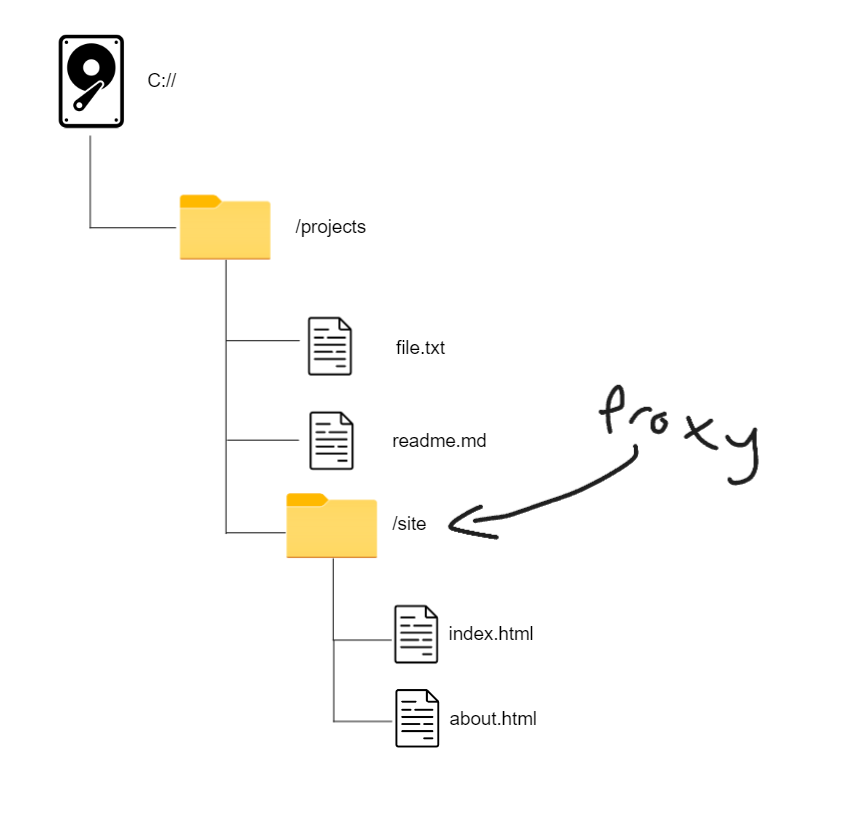

URL’s are what you use to access websites. For examplle this page is on https://schulichignite.com/definitions/paths and this looks pretty familiar! It’s very similar to file paths, and in the old days it actually was. Old servers used to just proxy a folder. What that means is you would have some domain like example.com, that domain would then act like a current working directory from which people would then specify the HTML file they wanted to see! So if we had something like this, where the proxy is on /site:

Then when users go to example.com they would get index.html (reserved name for historical purposes), then if they went to example.com/about they would get about.html!

MIME Types

The web almost completely ignores extensions. Instead the web uses MIME types. For details about how these work, check out this page